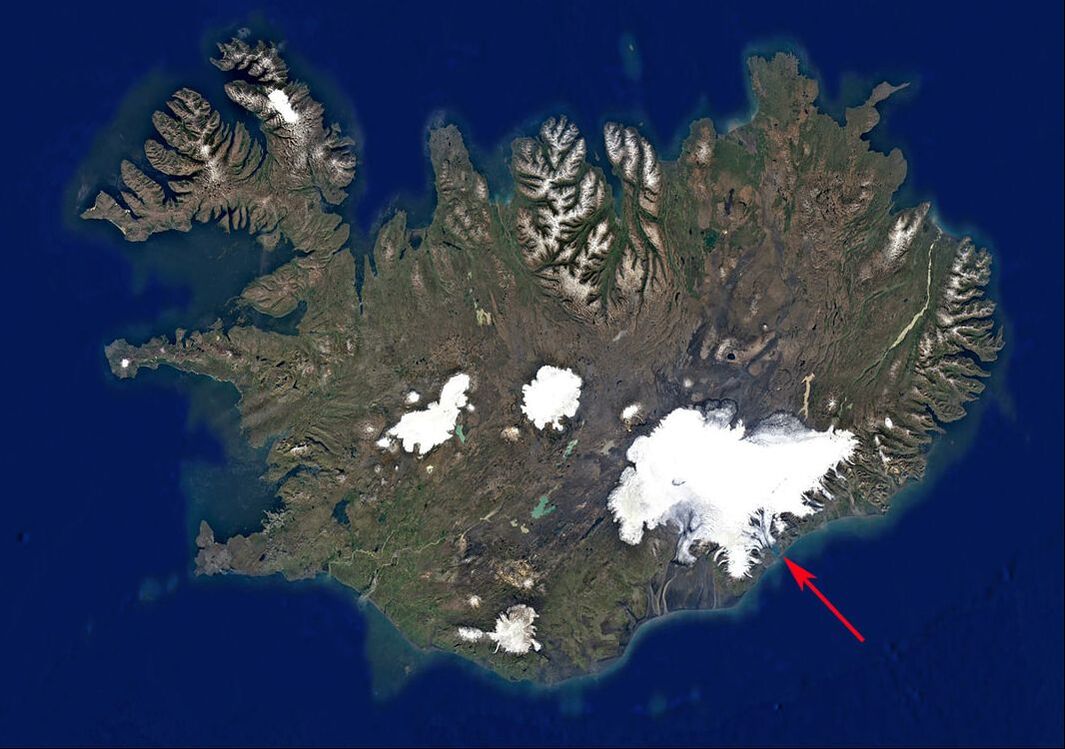

Vatnajökull National Park encompasses the entire Vatnajökull glacier and the surrounding area. The park is a World Heritage Site because of its cultural, historical and scientific significance. The glacier, which is around 1,800 feet thick, hides a number of mountains, active volcanoes, valleys and plateaus. On the southeastern edge of Vatnajökull, a glacial tongue, called Breiðamerkurjökull, extends into a lagoon that flows into the Atlantic Ocean.

The first settlers arrived to this part of Iceland around 900 AD when Breiðamerkurjökull glacier could be found spreading twelve miles further north beyond its present location. The glacier continued to grow through the 18th and 19th century. The last structure that the glacier destroyed during its expansion was in 1702 when it crushed a local resident’s farm. The glacier was named after this family, the Breiðamörks. In the 1890’s, the glacier started to melt and retreat back up the valley. By the 1900's, it had moved 3.5 miles. In early 1930’s, the retreating glacier a created a depression and the melting ice filled the lagoon, named Jökulsárlón. As the temperatures increased during the later part of that century, the lagoon became a lake as more of the glacier retreated and continued to melt. The lake more than doubled in size between 1975 to 2004 and increased it’s depth to 660 feet making it the deepest lake in Iceland. The tip of the glacier now floats on the lake and calving happens regularly throughout the warmer months producing icebergs of various sizes. The icebergs last for around five years in the lagoon where they stay until they are small enough to flow through the narrow passage that connects to the Atlantic Ocean.

The first settlers arrived to this part of Iceland around 900 AD when Breiðamerkurjökull glacier could be found spreading twelve miles further north beyond its present location. The glacier continued to grow through the 18th and 19th century. The last structure that the glacier destroyed during its expansion was in 1702 when it crushed a local resident’s farm. The glacier was named after this family, the Breiðamörks. In the 1890’s, the glacier started to melt and retreat back up the valley. By the 1900's, it had moved 3.5 miles. In early 1930’s, the retreating glacier a created a depression and the melting ice filled the lagoon, named Jökulsárlón. As the temperatures increased during the later part of that century, the lagoon became a lake as more of the glacier retreated and continued to melt. The lake more than doubled in size between 1975 to 2004 and increased it’s depth to 660 feet making it the deepest lake in Iceland. The tip of the glacier now floats on the lake and calving happens regularly throughout the warmer months producing icebergs of various sizes. The icebergs last for around five years in the lagoon where they stay until they are small enough to flow through the narrow passage that connects to the Atlantic Ocean.

This time lapse video provides an overview of the retreating glacier and the formation of the lake between 1984 and 2019.

|

|

|

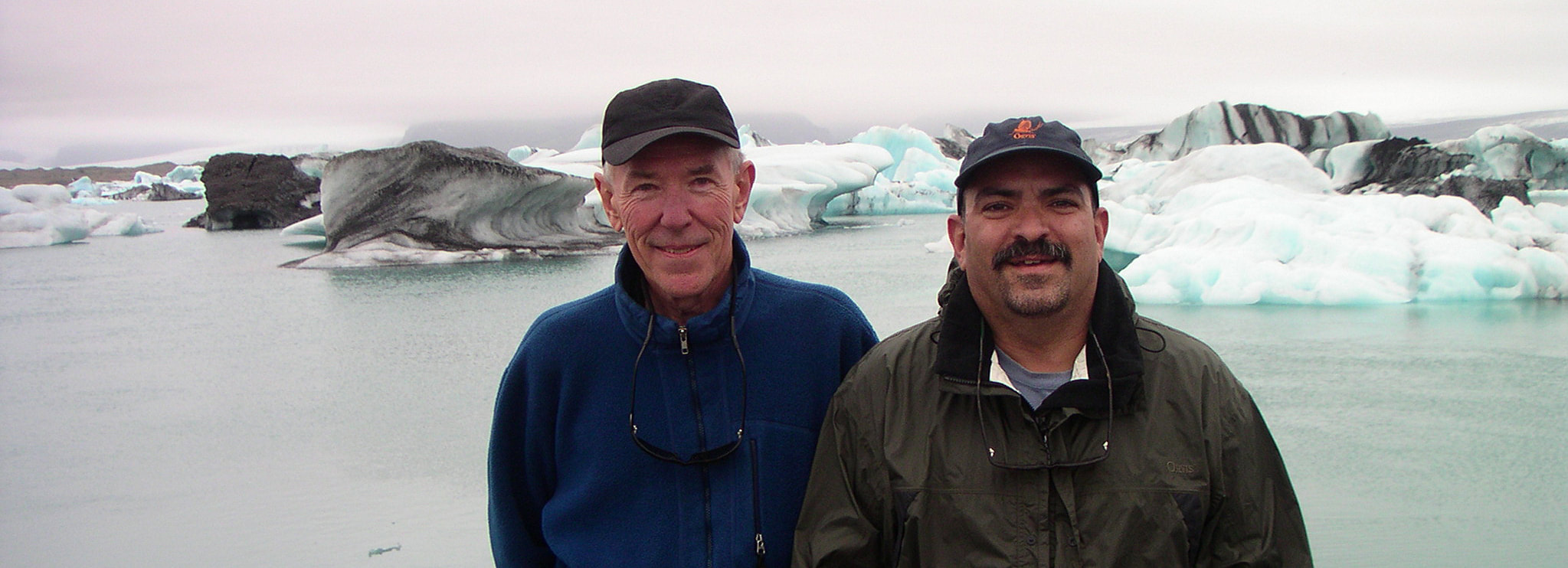

The Lost Beauty: Iceberg Series started in 2003 on my second trip to Iceland when I visited the lagoon for the first time with a friend, Ray McLain. Ray and I were on our way to fly fish the Breiðdalsá when we came across Jökulsárlón. It was a shocking site to see the large icebergs floating so close to the shoreline. There was also something sad about the 2,500 year ago icebergs slowly dying in front of us. Each seemed to possess their own identity and spirit. I took photographs of the icebergs thinking that somewhere down the road I might produce a body of work in dedication to them.

A decade passed before I returned with my family to visit a new group of icebergs floating in the lagoon. The mood was more joyous as I was able to experience the wonder of nature through the eyes of my children and wife. I was on a writing assignment for a magazine so I was able to arrange a private tour of the lagoon on a small inflatable zodiac which brought me right next to the icebergs. As the ice sculptures loomed overhead, we could see the remainder of the iceberg under the raft .

There was a sense of danger and excitement as we approached each iceberg since we knew that they could capsize at any moment and crush us into the freezing water. After the initial panic wore off, there was a sense of peace and connectiveness to the icebergs as I realized that this would be the last time that I would see each iceberg again. I continued to take photographs reaffirming my desire to create a series of paintings and, perhaps, a book in homage to them and as an educational tool to bring some more awareness to the causes that were affecting this region bordering the Arctic Circle. Breiđamerkurjökull glacier has responded more severely than many other regions from around the world due to unstable climates and rain events. It has has lost over 11 % of its land mass which is one of the highest amounts lost from all glaciers in the world.